TV premiere week has come and gone. Veni, video, vici, as they used to say at MTV.

I am not unhappy with this season’s televised offerings. Nevertheless, I would trade any (perhaps all) of the shows currently on the air for a few episodes of Burns and Allen.

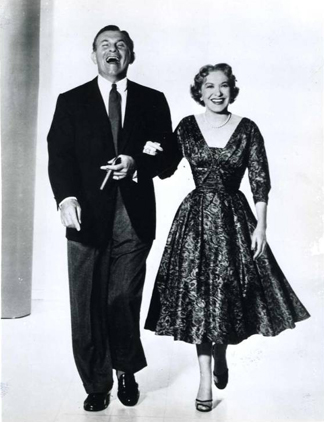

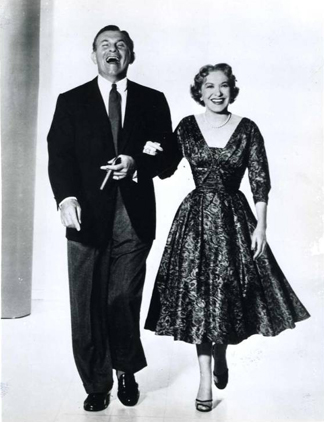

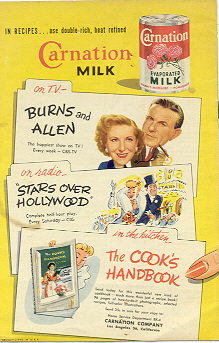

The George Burns and Gracie Allen Show celebrates its diamond anniversary today. It debuted on CBS on October 12, 1950.

George Burns and Gracie Allen were hardly strangers to entertainment when their television program went on the air.

The two had worked together for almost 30 years in vaudeville, in films, and on the radio—and each went through years of show-business experience separately before their meeting in 1922 (or 1923; accounts vary).

In some ways, the basics of their act had barely changed over the years. As always, Gracie played a “dumb Dora” character whose reworking of facts and words amused audiences. As her straight man George cued audiences on how to interpret her zaniness.

Nevertheless, the pair incorporated a few changes into their television show, which was written by George Burns himself along with an experienced stable of writers.

First, George’s character steps out of the action of the show to address the audience and comment on the plot. He is part stage manager, part actor, part Greek chorus, part narrator, and part master of ceremonies.

Second, the pair played “themselves,” celebrity performers George Burns and Gracie Allen, living in Beverly Hills, California, not just characters named George and Gracie.

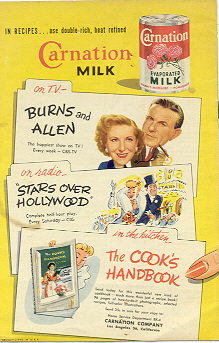

Eventually, their son Ronnie joined the cast as himself. Their announcer (first Bill Goodwin and later Harry Von Zell) played their announcer, who extols the virtues of the sponsors’ products, most notably Carnation Evaporated Milk.

Gracie is always fascinated by the idea of getting milk from carnations.

Early on in the series, George’s narrator observes that the show has “more plot than a variety show and not as much as a wrestling match.” In fact, the plot is generally set off by one of Gracie’s misunderstandings—or, as I like to call them, reinterpretations–of a situation.

The plot is resolved when it is time to end the episode, often in a rather cursory manner. For example, George once settles a court battle by informing the judge that he will never work on The Burns and Allen Show again if he doesn’t wind up the case in a hurry.

A fairly typical plot comes in an episode titled “We’re Not Married” in which Gracie and her loyal friend Blanche Morton (played by Bea Benaderet) have just seen the Ginger Rogers film of that title. It revolves around the discovery by a number of couples that the judge who married them several years earlier forgot to renew his license.

Gracie observes that the judge in the movie (played by Victor Moore) looks like the judge who married her to George—and promptly jumps to the conclusion that she and George have never really been married.

When George informs her that Victor Moore didn’t marry them, she only responds, “Why didn’t you tell me then? I could have spent our honeymoon looking for a husband.”

George tries a number of tricks to get Gracie to believe that they are legitimately married, eventually importing his best man, Jack Benny, to argue his case.

A bare plot synopsis doesn’t capture the magic of Burns and Allen. I could give you many reasons for watching it and, I hope, loving it. Here are three.

First, despite—or perhaps because of—the decades Burns and Allen spent working with similar material, the couple’s performances are amazingly fresh. George Burns is obviously having the time of his life. And Gracie Allen is such a strong actress that her character’s “illogical logic” comes across as authentic and rather sweet.

Second, the program presents a delightfully egalitarian view of marriage. George’s character never talks down to Gracie—or if he does, he regrets it. Their marriage, like their ongoing vaudeville routine, is one long conversation between people who may not always understand each other but clearly always love, respect, and enjoy each other.

Finally, I love the way Burns and Allen explores the push-pull between narration and language, between linear thinking and intuition.

George’s straight man/narrator should be in control of the plot; he has many more lines than Gracie and knows far more about what is going on in each episode than she does. He works hard to entertain viewers.

Nevertheless, Gracie’s character derails every single plot (and delights every viewer) with absolutely no visible work, simply by being herself and challenging the meaning of a few words. George’s reassertion of the logic of narrative at the end of each episode never has the power of Gracie’s disruptions of the plot and their life. And linearity never quite rules.

Gracie Allen’s health and a desire to live a quiet life after years of nonstop work led her to retire in 1958. Her heart gave out in 1964. It took George Burns years to regain a foothold in the entertainment world without her. He finally made it as a solo artist in 1975, when he won an Academy Award for playing an elderly vaudeville veteran in The Sunshine Boys.

Anecdotes about his late wife and the daffy character she played continued to pepper his stand-up work and the books he wrote until he died in 1996, having just fulfilled his ambition to turn 100.

It’s hard to determine the accuracy of any of those anecdotes. In the foreword to George Burns’s book I Love Her, That’s Why, his pal Jack Benny wrote:

Some of the episodes [related by George] I’m sure are true. Some of them will have a basis of truth and then will develop into the damndest lies you have ever read…. Sometimes at a party when [George] is telling a long story about me, he is so convincing that I have to take him into the other room and say, “Did that really happen to me?” He says, “Of course not. It was Harpo Marx, but Harpo isn’t here and you are.

In the case of George Burns and Gracie Allen, the only truth one can discern with certainty is that the pair loved each other, on and off the television screen. And that’s probably the only truth that matters.

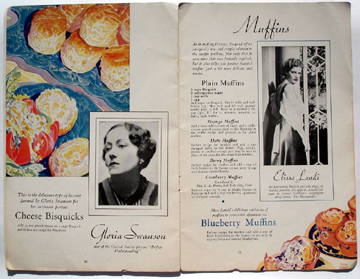

Although Gracie Allen’s TV character doesn’t spend a lot of time cooking, she does enter the kitchen from time to time, with predictably confusing results.

My friend Jack recently reminded me that one of Gracie’s signature dishes is roast beef. She preheats the oven and puts in one large roast and one small roast. When the little one burns, the big one is done.

Naturally, the character spends a lot of time cooking with evaporated milk, even if she never does figure out how to milk a carnation. Announcer Bill Goodwin is fond of pumpkin pie made with evaporated milk. (For a variation on this recipe, see last year’s “Pumpkin Pie Plus” recipe.)

I decided to make my own evaporated-milk dish. I was inspired by my friend Kelly Morrissey, who told me she had made roasted butternut squash into a lovely pasta sauce with the addition of spices and a little cream.

If you want to use cream instead of evaporated milk in this recipe, please do; I love cream! The evaporated milk was actually quite tasty, however.

The squash gives the dish a lovely color, a delicate flavor, and a remarkably smooth consistency.

Ingredients:

1 small to medium butternut squash, cut into 1-inch cubes

2 cloves garlic, minced

several sprigs of sage, cut into small pieces

olive oil, salt, and pepper as needed

3/4 cup water

1/2 teaspoon grated nutmeg

1 cup evaporated milk, plus up to 3/4 cup more as needed (if you’re making the dish with cream, use plain milk for the additional moisture)

a generous dash of cayenne pepper

1 pound pasta, cooked according to package directions (I used wagon wheels because I find them entertaining and not too big to handle)

3 cups grated sharp cheddar cheese (or to taste)

several sprinkles of paprika

Instructions:

In a Dutch oven at moderate temperature (350 degrees), roast the squash pieces uncovered, garlic, and sage in the olive oil, adding salt and pepper generously.

When the squash begins to soften, pour the water into the dish and stir. Cover and continue to cook until the squash softens completely. The cooking time should take somewhere between 30 minutes and 1 hour, depending on the age and density of your squash.

Remove the pot from the oven and allow it to cool for a few minutes. (Leave the oven on.) Carefully ladle the solids and liquids into a food processor or electric mixer, and mix until smooth. Mix in the nutmeg, 3/4 cup evaporated milk, and cayenne.

Grease a 2- to 3-quart casserole dish, and combine the cooked pasta and most of the cheese in it. Stir in the squash mixture. Your dish should be moist but not swimming in liquid. If it is not moist enough, add more milk. Top with the remaining cheese and the paprika.

Bake for half an hour. Serves 8 to 12.